Click here for the Online Article

Full article and issue available in the US on January 11, 2011

by Vanity Fair January 5, 2011, 12:01 AM

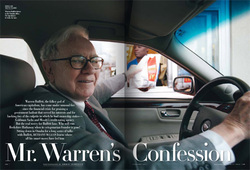

The future of Berkshire Hathaway is the subject of intense speculation throughout the financial world, for millions of investors and at the company itself. “It is all we talk about [at board meetings],” Warren Buffett tells Vanity Fair’s Bethany McLean, who spent 11 hours in Omaha with the octogenarian Berkshire Hathaway C.E.O. to discuss who might lead the company he founded when, as David Sokol, one of his executives, puts it, “the bus hits.” Buffett, who has no plans to retire, tells McLean that he “tap dances to work.” His partner and vice-chairman for more than 40 years, Charlie Munger (who, at 86, is not a contender) also speaks to McLean for a profile that provides an in-depth look at Warren Buffett’s thinking on succession as well as the possible choices. Buffett also talks to Vanity Fair about the evolution of his investment strategy, his trust in the wisdom of American capitalism, his “pragmatic” investment style, and belief in luck.

With Buffett’s offspring out of the running, there is no heir apparent for a company whose identity is deeply tied to its founder. Buffett himself describes Berkshire Hathaway as his work of art. “I’m getting to paint my own painting,” he tells McLean, “and if I’m using red, no one is saying, ‘Why don’t you use a little more blue?’ It’s enormous fun. I get applause. I like it when people cheer for my painting.” Still, Buffett assures McLean that Berkshire Hathaway will go on without him and that he has made provisions for this. “There is no end point for Berkshire Hathaway,” he says. “The important thing is not this year or next year, but where Berkshire is 20 years after I die. Not taking care of Berkshire would be like not having a will—cubed.” Sokol tells McLean that the company is “60 percent Warren Buffett and 40 percent Berkshire Hathaway,” but adds, “The culture will have to make that 100 percent over time.” Buffett also speaks of the enduring Berkshire Hathaway “culture”: “There will be a lot of things built in to make sure that if something is really eroding the culture, then changes can be made,” he says.

“This much,” McLean writes, “is known: the roles of the chief investment officer . . . and the chief executive officer . . . both of which are now filled by Buffett, will be split between at least two people, and probably more.” There are rumored to be at least four C.E.O. candidates (the “most important” of his two roles, according to Buffett), all from inside Berkshire Hathaway. Sokol, a fellow Nebraskan, “is the top pick of most Buffett-watchers,” McLean writes. His number two, Greg Abel, is another name that is often mentioned. Ajit Jain, a Buffett lieutenant “with whom Buffett talks almost every day,” and Matthew Rose, who runs Burlington Northern, a Berkshire Hathaway-owned company, are the other possibilities.

“Finding a C.I.O. has proven even more challenging. Apart from the issue of skill, there’s the issue of personality,” McLean writes. Buffett says: “Take all the people with a great track record [in investing] over the past five years. I wouldn’t consider 95 percent of them.” Last July The Wall Street Journal reported that Buffett had his eye on Li Lu, a 1989 Tiananmen Square protest leader turned hedge-fund manager. On that matter, McLean reports, “all Buffett will say is that Li preferred to stay where he was.”

Buffett discusses the private-equity way of investing, which he calls “love of money over love of business.” Berkshire Hathaway is known for its hands-off approach to dealing with the companies it acquires, making them the “buyer of first resort.” Buffett admits to McLean that he detests stepping in, possibly to a fault. “There are things where I’ve had to get involved, but I’ve usually done it through other people,” he says. “Every time I am later than I should be. It’s the only thing about my job that I hate. I would give up a big percentage of my net worth if I didn’t have to do this. I hate it. Therefore, I put it off and I procrastinate.”

The lifelong Democrat, who recently announced that he was donating the majority of his wealth to the Gates Foundation, came under fire for a New York Times op-ed piece he wrote in November thanking the Bush administration for the Wall Street bailout. “I felt that they deserved thanks,” he tells McLean. “People should see that the government can do things right.” He adds, “I may not have convinced anyone, but it should mean something when I say George Bush was right!” Bush’s September 2008 declaration “If money isn’t loosened up, this sucker could go down!” Buffett calls “the 10 most immortal words in the history of economics.”

Warren Buffett gave Vanity Fair an advance look at his 2011 letter to shareholders, which goes out in March. In it he quotes a missive from his grandfather, who believed in keeping some cash on hand for emergencies. “For your information, I might mention that there has never been a Buffett who ever left a very large estate,” Earnest Buffett tells his descendants, “but there has never been one that did not leave something. They never spent all they made.” The letter to the shareholders will also address last year’s hire of 39-year-old Todd Combs, who could one day be the C.I.O. of Berkshire Hathaway. “Our goal was a two-year-old Secretariat, not a 10-year-old Seabiscuit,” Buffett plans to write, adding, “Not the smartest metaphor for an 80-year-old C.E.O.”

Rivaling Buffett’s confidence in Berkshire Hathaway is his faith in the United States. “We had four million people here in 1790,” he tells Vanity Fair. “We’re not more intelligent than people in China, which then had 290 million people, or Europe, which had 50 million. We didn’t work harder, we didn’t have a better climate, and we didn’t have better resources. But we definitely had a system that unleashes potential. This system works. Since then, we’ve been through at least 15 recessions, a civil war, a Great Depression…. All of these things happen. But this country has optimized human potential, and it’s not over yet. It’s like what’s written on the tomb of Sir Christopher Wren: If you seek his monument, look around you.”

The February issue of Vanity Fair is available on newsstands in New York and L.A. on Thursday, January 6, and nationally and on the iPad on Tuesday, January 11.

Full article and issue available in the US on January 11, 2011

by Vanity Fair January 5, 2011, 12:01 AM

The future of Berkshire Hathaway is the subject of intense speculation throughout the financial world, for millions of investors and at the company itself. “It is all we talk about [at board meetings],” Warren Buffett tells Vanity Fair’s Bethany McLean, who spent 11 hours in Omaha with the octogenarian Berkshire Hathaway C.E.O. to discuss who might lead the company he founded when, as David Sokol, one of his executives, puts it, “the bus hits.” Buffett, who has no plans to retire, tells McLean that he “tap dances to work.” His partner and vice-chairman for more than 40 years, Charlie Munger (who, at 86, is not a contender) also speaks to McLean for a profile that provides an in-depth look at Warren Buffett’s thinking on succession as well as the possible choices. Buffett also talks to Vanity Fair about the evolution of his investment strategy, his trust in the wisdom of American capitalism, his “pragmatic” investment style, and belief in luck.

With Buffett’s offspring out of the running, there is no heir apparent for a company whose identity is deeply tied to its founder. Buffett himself describes Berkshire Hathaway as his work of art. “I’m getting to paint my own painting,” he tells McLean, “and if I’m using red, no one is saying, ‘Why don’t you use a little more blue?’ It’s enormous fun. I get applause. I like it when people cheer for my painting.” Still, Buffett assures McLean that Berkshire Hathaway will go on without him and that he has made provisions for this. “There is no end point for Berkshire Hathaway,” he says. “The important thing is not this year or next year, but where Berkshire is 20 years after I die. Not taking care of Berkshire would be like not having a will—cubed.” Sokol tells McLean that the company is “60 percent Warren Buffett and 40 percent Berkshire Hathaway,” but adds, “The culture will have to make that 100 percent over time.” Buffett also speaks of the enduring Berkshire Hathaway “culture”: “There will be a lot of things built in to make sure that if something is really eroding the culture, then changes can be made,” he says.

“This much,” McLean writes, “is known: the roles of the chief investment officer . . . and the chief executive officer . . . both of which are now filled by Buffett, will be split between at least two people, and probably more.” There are rumored to be at least four C.E.O. candidates (the “most important” of his two roles, according to Buffett), all from inside Berkshire Hathaway. Sokol, a fellow Nebraskan, “is the top pick of most Buffett-watchers,” McLean writes. His number two, Greg Abel, is another name that is often mentioned. Ajit Jain, a Buffett lieutenant “with whom Buffett talks almost every day,” and Matthew Rose, who runs Burlington Northern, a Berkshire Hathaway-owned company, are the other possibilities.

“Finding a C.I.O. has proven even more challenging. Apart from the issue of skill, there’s the issue of personality,” McLean writes. Buffett says: “Take all the people with a great track record [in investing] over the past five years. I wouldn’t consider 95 percent of them.” Last July The Wall Street Journal reported that Buffett had his eye on Li Lu, a 1989 Tiananmen Square protest leader turned hedge-fund manager. On that matter, McLean reports, “all Buffett will say is that Li preferred to stay where he was.”

Buffett discusses the private-equity way of investing, which he calls “love of money over love of business.” Berkshire Hathaway is known for its hands-off approach to dealing with the companies it acquires, making them the “buyer of first resort.” Buffett admits to McLean that he detests stepping in, possibly to a fault. “There are things where I’ve had to get involved, but I’ve usually done it through other people,” he says. “Every time I am later than I should be. It’s the only thing about my job that I hate. I would give up a big percentage of my net worth if I didn’t have to do this. I hate it. Therefore, I put it off and I procrastinate.”

The lifelong Democrat, who recently announced that he was donating the majority of his wealth to the Gates Foundation, came under fire for a New York Times op-ed piece he wrote in November thanking the Bush administration for the Wall Street bailout. “I felt that they deserved thanks,” he tells McLean. “People should see that the government can do things right.” He adds, “I may not have convinced anyone, but it should mean something when I say George Bush was right!” Bush’s September 2008 declaration “If money isn’t loosened up, this sucker could go down!” Buffett calls “the 10 most immortal words in the history of economics.”

Warren Buffett gave Vanity Fair an advance look at his 2011 letter to shareholders, which goes out in March. In it he quotes a missive from his grandfather, who believed in keeping some cash on hand for emergencies. “For your information, I might mention that there has never been a Buffett who ever left a very large estate,” Earnest Buffett tells his descendants, “but there has never been one that did not leave something. They never spent all they made.” The letter to the shareholders will also address last year’s hire of 39-year-old Todd Combs, who could one day be the C.I.O. of Berkshire Hathaway. “Our goal was a two-year-old Secretariat, not a 10-year-old Seabiscuit,” Buffett plans to write, adding, “Not the smartest metaphor for an 80-year-old C.E.O.”

Rivaling Buffett’s confidence in Berkshire Hathaway is his faith in the United States. “We had four million people here in 1790,” he tells Vanity Fair. “We’re not more intelligent than people in China, which then had 290 million people, or Europe, which had 50 million. We didn’t work harder, we didn’t have a better climate, and we didn’t have better resources. But we definitely had a system that unleashes potential. This system works. Since then, we’ve been through at least 15 recessions, a civil war, a Great Depression…. All of these things happen. But this country has optimized human potential, and it’s not over yet. It’s like what’s written on the tomb of Sir Christopher Wren: If you seek his monument, look around you.”

The February issue of Vanity Fair is available on newsstands in New York and L.A. on Thursday, January 6, and nationally and on the iPad on Tuesday, January 11.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed